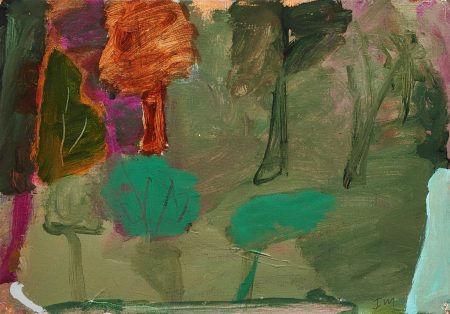

Idris Murphy. Backblocks.

Survey exhibition of works.

On now until Sunday, 26 March, 2023.

Reviewed by Anthony Frater (Arts Wednesday)

Idris Murphy was born in Sydney in 1949 and graduated from Sydney’s National Art School in 1971. After receiving a succession of awards culminating in the Australian Arts Council Special Travel Scholarship in 1976 and the Dyason Bequest fund for Australian Artists Overseas in 1977-79, he traveled and studied widely in the United Kingdom, Ireland France and America. Since 1974 he has been Artist in residence at varying times in Melbourne, Sydney, Paris, London and Ireland.

His solo exhibitions have been plentiful and prolific and he has also been included in many ‘select group exhibitions’ both in Australia and overseas. His work is represented in The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Artbank, The Bibliotheque National de Paris, The National Gallery of Australia, The National Library of Australia, Parliament House in Canberra, The Telecom Collection and many other Corporate and Private collections nationally and internationally.

Following his return from abroad in 1979, Murphy was keen to continue the Australian Landscape painting tradition, he said he wanted, “to come to terms with, to re invent and create symbolic images, metaphors, for a unique land…to evoke the essence of the landscape, accept its realness yet capture its otherness, its ‘something elseness’ – to encounter not just to observe”.

Indeed, to see his pictures makes one want to rush out at once to a land called Mutawintji in far western New South Wales, or Gondwana Land or Fowlers Gap and in the words of Robert Louis Stevenson, “ feel the needs and hitches of our life more nearly, to come down off the featherbed of civilisation and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints”.

Murphy’s work reveals to us a timeless landscape and despite the fact that there are solid figurative elements and discernible forms in many of his works that nonetheless float and hover, fixed and distorted through an outback haze, his idiom for the most part is one of Abstract Expressionism and is well served by a contrived fortuitous terra-morphism in that his interpretation of perspective, form and reality are deeply altered and shifted so that what is manifested becomes a metaphor or symbol for the obvious or banal.

He works at an easel en – plein air or in the studio using a range of brush sizes, even sticks, with which he freely applies broad flat expressive washes of somewhat primal, unexpected combinations of acrylic colour such as, “acidic reds and greens, pushed up against purple-pink and a dark, murky blue“. There is a rough instinctive but introspective spontaneity and fluidity to his painterly style contrasted with light gesso textures that give the work a sense of depth, movement and enduring timelessness. He uses a mixed media: collage (strips of paper or tree bark), pencil, charcoal, and acrylic paints. He also from time to time applies small areas of thick highly textured paint that act as a foil or purposeful slave to pictorial balance and harmony. At times one can even see the white canvas, or paper, underneath.

His work is not just observed in the here and now but also draws on memory in an attempt to capture the shifting of time and place. One of the ways he achieves this is to push the painted form into the canvas or paper, say a tree; he freely impregnates it with a paint filled brush. He overlays a thin gesso wash and then drags or scrapes a broad metal wedge across the surface of it so that the remaining form recedes, smudged ghost like into the background to become a reflective remnant of memory which now, impregnated as it is, conversely infuses and manifests upon the present. It gives his work a timeless enduring permanence that typifies the Australian landscape which is also “spiky and difficult”, shimmering, ancient and unwavering in its determination to prevail waxing and waning into eternity.

Murphy’s work is like an alchemic metaphor in that a profound transformation or metamorphosis occurs between what he observes and what is expressed on the canvas. He has a Cézanne style determination to get to the essence or the crux of his motif, not just the rock or the tree or the mountain or for that matter himself, but the intrinsic symbiotic connectedness of all these things, that elusive essence, a spirit, a higher truth.

He is interested in reintroducing divinity back into painting and though he is emphatically quick to point out that it has little to do with an “overtly religious experience”, he says …“the silence in the outback conveys something to me about God’s intent, but that’s not enough, I am trying to make that palpable again… re-cognized, re-recognized in paintings ”.

Drury quotes Australian Expressionist Kevin Connor who said of Murphy, “his work has matured into a line of visual thought of great significance to the art of this country”. Art Critic, Bruce James of the Sydney Morning Herald said “his paintings have the force of talismans brought back from the site of their creation. Also from the Herald, John McDonald finds parallels between Murphy’s work and a Romantic landscape painting in that, “like the Romantics, looking at the natural world also becomes a looking within the self, or the search for a relationship with the Creator of both self and world. One could adopt a more formal, secular perspective, but the brooding nature of his imagery suggests a deeper source of motivation“.

One does not need to look too deeply to find that there is a nexus between the work of Idris Murphy and that of the Indigenous Australian artists. It could be seen as: spiritual ‘white man’ within his own frame of reference and all that entails, reinterpreting the spirit that has always existed in outback Australia, or, The Dreamtime. The spiritual connection between the two is not only striking but historically familiar, like the change over from Ancient Greek and Roman Mythology, to Catholicism.

Finally, Literary figure Jacques Delaruelle said Murphy, “shows the grounding of thought in perception, and in doing this, “makes it clear that the spirit hides neither inside nor outside the body, but is very much mingled with things”, and that , “the work itself does not purport to describe external appearances on a conventional or an objective basis. It is not mimetic, yet it seeks as if in the dark for a point of contact with an all encompassing presence“.

On now until Sunday, 26 March, 2023.