By Elisa Herrera

Australia stands divided on the 26th of January, as celebrations and mourning unfold simultaneously. While officially declared as Australia Day since 1994, it’s evident that this date doesn’t uniformly unite the nation.

In contrast to the segment that enjoys parties, barbecues, and a day off work, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals—and a growing number of non-Indigenous allies who stand in solidarity—experience the day as one of commemoration. Known as Invasion Day or Survival Day, it serves as a solemn acknowledgment of historical complexities, emphasizing the imperative need for recognition and understanding.

Historical Insights

Some assert that 26 January commemorates the First Fleet’s landing, when English convicts first arrived in Australia in 1788. However, the fleet initially reached Botany Bay around a week earlier (between 18-20 January) before relocating further north due to the bay’s unsuitability.

The 26th signifies the fleet’s arrival at Sydney Cove, a pivotal moment marked by Captain Arthur Phillip raising the Union Jack flag, officially declaring British sovereignty over half of Australia.

Yet, this territory had long been inhabited by Australia’s first people—known as Aboriginal Australians—who had thrived on the continent for over 65,000 years.

Following the British arrival, cultural traditions were systematically suppressed, resulting in the eventual loss of many. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the era of colonization brought forth a devastating period marked by massacres, violence, the spread of diseases, and profound losses.

Researchers have meticulously documented a minimum of 270 massacres of Aboriginal Australians throughout the initial 140 years of Australia’s history. This grim record underscores a distressing chapter marked by widespread violence against the indigenous population.

In the 1900s, a deeply troubling practice unfolded as numerous Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families and communities. It is estimated that as many as 1 in 3 Indigenous children experienced forced removal to be raised in institutions, fostered out or adopted by non-Indigenous families, nationally and internationally. This painful chapter, often referred to as the Stolen Generations, has had lasting and profound effects on the affected individuals, families, and communities.

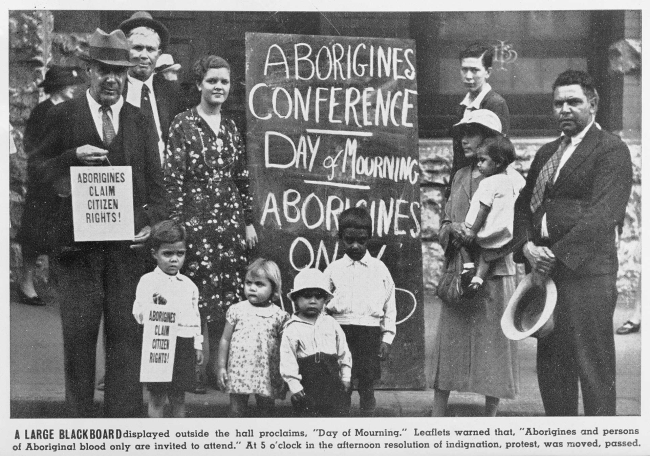

As a consequence, the resistance to celebrating January 26 has a longstanding history. As early as 1938, Aboriginal activists declared it a Day of Mourning, marking a poignant moment in the ongoing opposition to the date. This historical resistance is deeply rooted in the acknowledgment of the traumatic experiences endured by Indigenous communities, encompassing massacres, forced removal of children, and other injustices perpetuated during Australia’s colonial history.

Present Reality

Amid the scorching heat of Sydney, the city found itself divided into two distinct scenes. One half reveled in the celebratory spirit, engaging in beach outings, parties, and a much-deserved break from work. This contingent exuded pride for their nation and celebrated the progress of their society. Meanwhile, the other half took center stage, with thousands gathering at Belmore Park on Gadigal land. Their purpose was clear—to march through the city and amplify their voices, creating a powerful and unified message.

Emotions ran high as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander speakers took the stage, delivering impassioned speeches that resonated with the collective frustration and sorrow of the attendees. The speeches delved into critical issues, including the alarming rates of incarceration, the persistent tragedy of deaths in custody, and the heartbreaking forced removal of First Nations children from their families.

These rallies unfolded just months after the resounding defeat of the proposal for an Indigenous voice to parliament in the referendum. Despite this setback, the spirit of the crowd remained undeterred.

Paul Silva, part of The Blak Caucus, brought to light the long history of state-sanctioned massacres of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people since 1788, emphasizing the collective trauma inflicted. “We don’t need a day that inflicts so much trauma on us,” he declared.

Resonance of Perspectives

In a conversation that delved into the heart of Australia Day’s complexities, Emma Rossi, ambassador of Australia Day, shared her perspective on fostering understanding and respect towards Indigenous communities.

Highlighting the National Australia Day Council’s dedicated efforts, Emma emphasized the commitment to inclusivity on this significant date. Specifically addressing Indigenous issues, she extended an invitation to delve into the rich history of Australia—an essential step towards fostering a deeper understanding:

Emma encourages a more profound discussion surrounding the change of date, where the purpose is thoroughly analyzed and contemplated. Her engagement extends beyond advocacy, as she actively invites individuals to embark on a journey of learning and introspection.

Having played a prominent role in the campaign for the “yes” vote during the referendum, Emma reflects on the unintended misunderstandings that arose. She candidly acknowledges, “We haven’t really acknowledged the true killing, and the pain that we have caused to First Nations people.” In these words, the ambassador underscores the importance of acknowledging historical truths and the shared responsibility towards reconciliation.

Australia Day Date Debate

As the nation grapples with the question of whether Australia Day’s date should change, transitioning from celebration to commemoration, diverse voices echo through the ongoing debate. Seeking insights from various corners, here’s what the voices of Australia had to say:

Suggested alternatives to the current date include significant milestones like the formation of the federation on 1 January 1901, the day Queen Victoria gave consent to the Constitution of Australia on 9 July, or the historical event of the Eureka Stockade on 3 December. Each proposed date carries its own historical significance, prompting a reevaluation of the narrative woven into Australia’s national day.

Yet, the debate remains complex and multifaceted. The discussions surrounding a potential change will likely persist on the national agenda, stretching into the year 2025 and beyond. As Australia navigates this crossroads, the ongoing dialogue reflects the nation’s commitment to grappling with its history and evolving identity.