31 May – 21 September 2025

Review by Anthony Frater (Arts Wednesday)

It’s always good to have a reason to visit Canberra and Cézanne to Giacometti, Highlights from the Museum Berggruen / Neue Nationalgalerie, is a jolly good reason. On now at the National Gallery of Australia until 21 September it’s a unique opportunity to see how Modern Art came into being, who influenced who and how that influence reached our own shores from Europe.

The timeline is never clear cut, different periods and genres always overlap but for simplicity, Modern Art truly began with the Impressionist painters – think Monet, Renoir, Pissarro. After a period of initial outrage and rejection it’s a movement that came to prominence and appreciation during the last quarter of the nineteenth century and despite sub genre after sub genre, the broad term ‘Modern Art’, has been used to describe artworks well into and for most of the twentieth century.

But change happens: painter techniques and methods, use of colour, composition and subject matter, but most of all, form and perspective was about to be transformed.

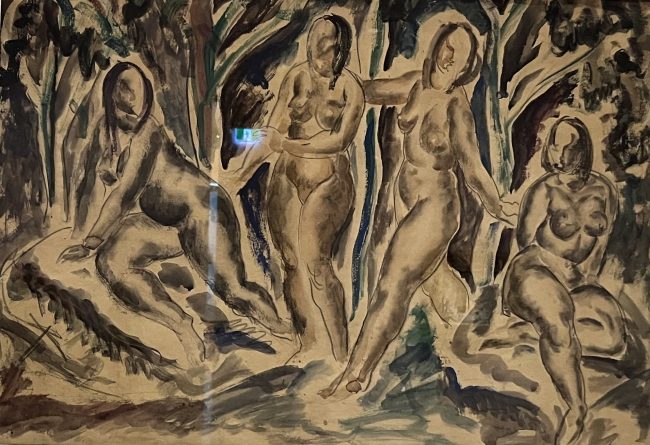

At the forefront of this change was French Post Impressionist artist, Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), and indeed the exhibition begins with his work. Cézanne made a very deliberate and clean break from traditional Classical methods and ideologies. He even re-evaluated the technical principals of his Impressionist contemporaries.

He rejected traditional ideas around the use of light and shadow: the sharp contrast between light and dark that was used traditionally to accentuate everything from form and mood to nuance and movement. He was also not interested in linear perspectives: formulaic techniques previously used to create the illusion of depth and distance on a flat surface; formulas that followed a scheme of imaginary parallel and horizontal lines that appear to converge at a single vanishing point on the horizon line making objects seem smaller as they recede.

Instead Cézanne experimented using individual brushstrokes, larger in the foreground, smaller as depth recedes; he would corral his work into geometric portions, work painstakingly within each portion then move onto the next. He also used colour, for example, warm colours brought elements in the landscape forward, while cool colours made them recede; thin washes of colour were used in the foreground, the middle, the background and sky, again using hues that matched his scheme to create depth. It’s arguable whether he succeeded or not and could explain why, to some, a lot of his paintings look flat.

Rejected for much of his life by the establishment, he was a liberationist and more a painter’s painter during his lifetime – revered as the ‘Sage’ by the avant-garde and the ‘father of modern art’ given his influence on Cubism. The establishment came to him later, it seemed to take a while for them to catch on to what his peers saw and soon knew. The art lover is happy to go along for both reasons with both camps but it’s questionable whether his aesthetic was ever as popular then or now and admired as that of say Picasso or Van Gogh (1853-1890), the admiration for Cézanne perhaps more technical.

The exhibition is divided into rooms, each coloured purposefully by what would seem like hues from Cézanne’s colour palette. Each room is dominated by one or more of the featured artists.

As you move through the exhibition, one reminds oneself it is not really a broad study on the subject but nonetheless significant enough. We learn about the influence his work and life had on all the painters included in this exhibition, and there are a some heavyweights – Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Paul Klee (1879-1940), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Georges Braque (1882-1963), and of course, Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966). We’re only left to wonder, where is Van Gogh? Our National Gallery has one Van Gough in its collection, the Museum Berggruen, none – it could explain why.

There were many surprises and one majorly breathtaking one. In Cézanne’s acidic mauve room I thought I was looking at another Cézanne only to read the wall text to find it was, Composition 1937 by Australia’s own, Russell Drysdale (1912-1981).

Difficult to pin down in terms of style, Paul Klee moved freely between figuration, landscape and abstraction and there are excellent examples of all. In his deep purple room with his cleverly coloured geometric abstractions, his focus on the way colour interacts, his scratchy mark making and bio morphed human forms one is imagining how his work might have influenced a painter such as Joan Miró (1893-1983), or perhaps visa versa.

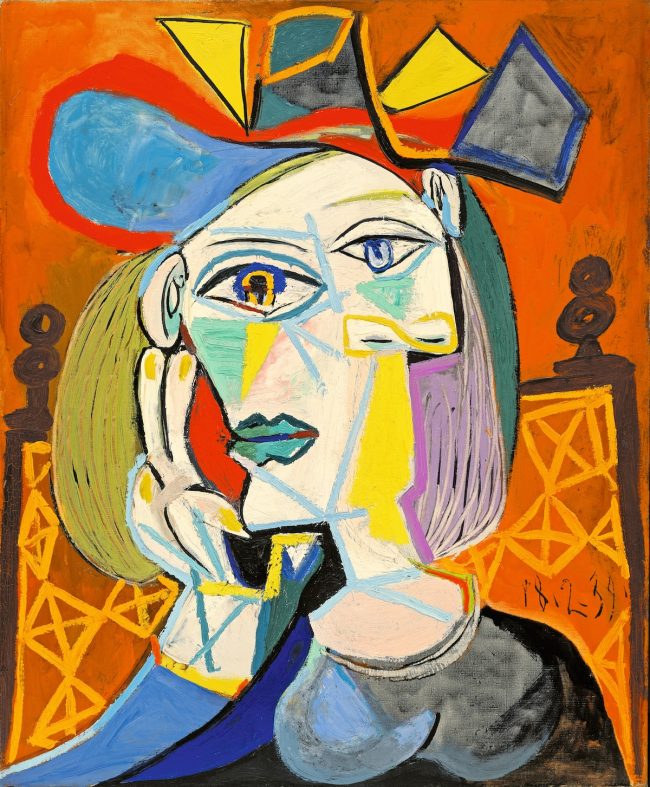

In Picasso’s mint green room from his Rose period we get the expressive manner and countenance on the face of his Seated Harlequin (1905) who wears a look, or is giving us a somewhat acerbic look – or is it melancholic – that could otherwise be interpreted in any amount of ways; it isn’t a look fit for any occasion lets say, and if we were ever in any doubt – Picasso could do realism! He was a brilliant draughtsman and drawer, very few come close to his ability to affect a true-to-life demeanour, an attitude or a stance – like say Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) — with the simple stroke of the brush. There are a number of them in this exhibition, and every bit if not more engaging than his more synonymous-with-Picasso cubist portraits.

Matisse is ironically in a white room, ironic because of his pioneering use of colour – used in ways that highlighted an emotion. He was an early ‘Fauvist’ and it would seem by what we see here, perhaps a hero to Pop artists given his brightly coloured at times graphic style. Nonetheless it’s the colour and graphic quality of a lot of the works that perhaps makes them look their best on a white background.

And finally, to what might be considered breathtaking… Giacometti’s Tall nude standing 111. A two meter sculpture on a plinth, adding more height, of a woman, tall and thin, so thin she is almost like a straight vertical line. As we approach she is dramatically framed by a cathedral like doorway, she stands right in the centre of it – she is tall and majestically statuesque. The room is darkened accentuated by the walls being a dark steel blue, she at one minute floats and hovers over all she perceives, the next she is unreachable, aloof – an impregnable armour – is she a saviour, a messiah? Shocking or not but she looks almost Christ like, in fact given the darkened room and the way she is lit gives her a smouldering effect and one is immediately seeing Velazquez’s Christ Crucified (1632), might be a stretch but ‘art is what the viewer says it is’.

One felt something for the Australian works – they were always at risk of becoming simply derivative. But in fact many Australian painters were in Europe at the time studying the latest techniques and exposed to all that was going on in the art scene in many places: Italy, France, England, Germany. Local Art schools taught the newest techniques; reproductions, books and reviews would be coming through from Europe, all teaching and talking about the latest post Impressionist/Modernist methods. The exhibition showcases Australian works from the Gallery’s own collection to thoughtfully demonstrate that influence.

This is an exhibition that really must be seen if one is interested in understanding Modern Art. It has some incredible works rarely seen in this country, particularly the works of Klee, Picasso and Giacometti. Cézanne’s influence on Modern Art and the artists who produced it is by now widely accepted. His work was admired by his peers throughout his life – they really did get what he was doing. It took longer for his fan base to grow and it’s usually the gallerists, connoisseurs and academics who initially would have been guilty of discarding his work as irrelevant, but then conversely drag everyone along with them in a belated fit of realisation and epiphany – this unfortunately more so after his death. What a fabulous few days in our wonderful Capital, what an exhibition – it doesn’t get much better.