29 June – 7 October 2024

Review by Anthony Frater. Arts Wednesday.

They say every picture tells a story and this exhibition tells us why. If you haven’t had a chance to get down to the National Gallery in Canberra to see the Paul Gauguin exhibition, better hurry because there are just three days left to see this truly wonderful, once in a life time exhibition.

Paul Gauguin (b. Paris, 7 June 1848, d. Marquesas Islands 8 May 1903) was a self taught French painter (ceramicist, printmaker, sculptor), well, actually let’s say he never attended formal classes but had some pretty heavyweight mentors, tutors and colleagues, among them C ézanne and Pissaro. Along with Cézanne and van Gogh he was one of the great post impressionists and like them, a trail blazing figure in the development of modern art.

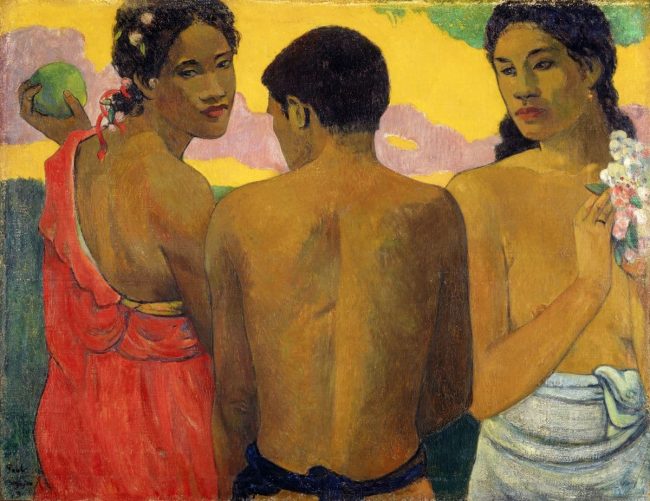

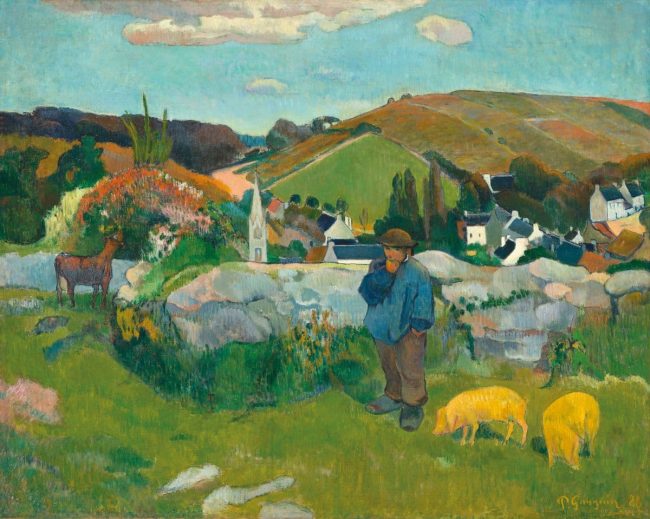

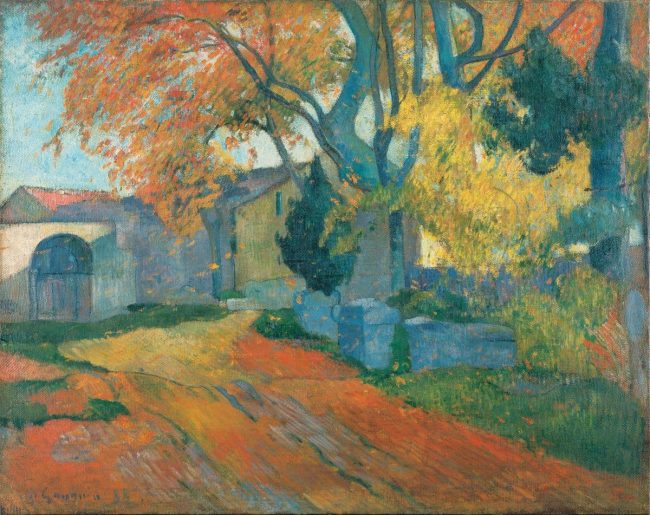

He began painting in his 20s, had a number of jobs – merchant seaman transferring to the French Navy, stockbroker – all of which he gave up to start painting full time. Unable to support his growing family he moved to Brittany from Copenhagen becoming the leader of a group of artists who were seduced by his strong ideas and his emphatic belief in himself as a painter. Then, influenced by the Barbizon School of painters, his subjects were ordinary people working in the fields at one and as part of the landscape – it was all about the glorification of honest toil and every day people – farmers, peasants and workers. In a break away from impressionism it was also here he developed a style where he would use areas of pure flat colour for expressive and symbolic purposes. At around this time he met art dealer and collector Theo van Gogh who encouraged him to visit his brother, Vincent, in Arles. The two like minded artists painted together but after a falling out they never saw each other again.

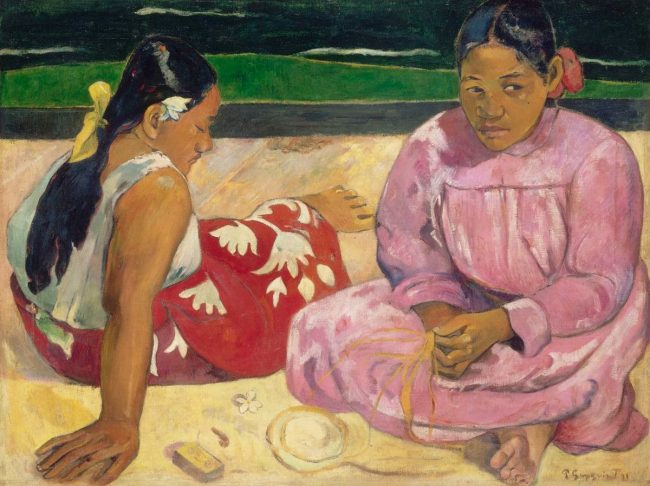

Probably most well known for his paintings of the landscape and people of Tahiti, his first time there was in 1891. Not long there he wrote: “I have escaped everything that is artificial and conventional. here I enter into truth, become one with nature. After the disease of civilisation, life in this new world is a return to health”. He really did want to come down off the featherbed of civilisation and deal with real people rather than the privileged higher classes in the cafes and nightclubs of downtown Paris. He was one of the first to find visual inspiration in the arts from primitive peoples.

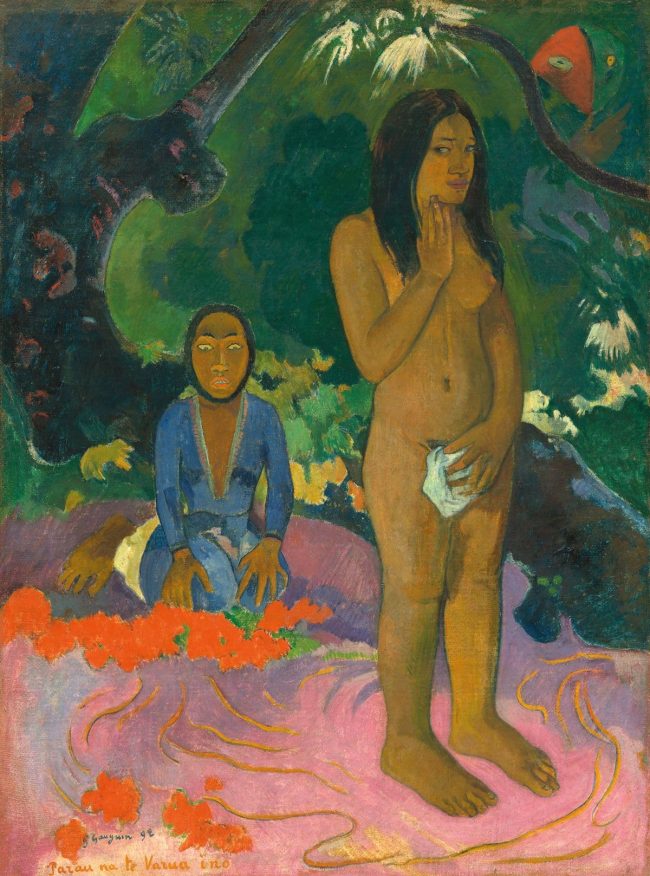

In Tahiti for just a couple of years he was forced to return to France due to poverty and ill health, both plagued him through out his life, but after inheriting some money he was able to return to Tahiti in 1895 – to go native again, to meditate, paint, create and live simply.

As a forerunner and inspiration to Fauvism he used a colour palette that was in many ways unnatural, it was all about decoration and matching colour to mood or emotion. In some of his works it would seem he was inspired by Japanese block prints: the foreground, middle ground and background are stacked as if on top of each other rather than using foreshortening techniques to create a perspective where the foreground, middle ground and back ground moves naturally away from the viewer into the distance.

In Tahiti his colours became more vivid, his drawing of figures almost mannerist, and his expression of human frailty, spiritual revelation and the mysteries of life became deeper, more profound – even spiritual. His seminal work, an allegory of life, where do we come from? who are we? Where are we going?, came just before a suicide attempt. He battled ongoing ill health (he had syphillis and it was this that was likely the primary cause of his death) and poverty and lack of recognition – the latter, like so many artists, came largely after his death, which is not to say he did not have any success in life. He once said, “I am a great artist and I know it. It is because I am that I have endured such suffering”.

Controversial legacies aside, Paul Gauguin lived a life of comfort and solace on the one hand, and torment and torture on the other – he did suffer for his art, his life’s passion. Such a rich life, such a rich body of work, this exhibition showcases everything he was and is to us today. It’s an incredibly important exhibition of work from one of the greatest artists in the canon of western art. The exhibition is a chronological diary, a pictorial diary of his art, his life, his loves and failures, his frailties and perhaps also his search for redemption – every picture really does tell a story.